|

|

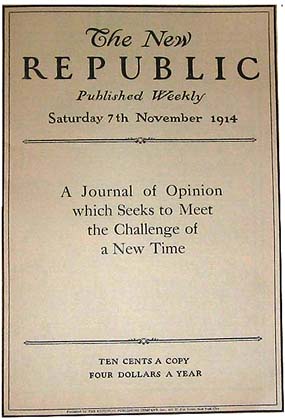

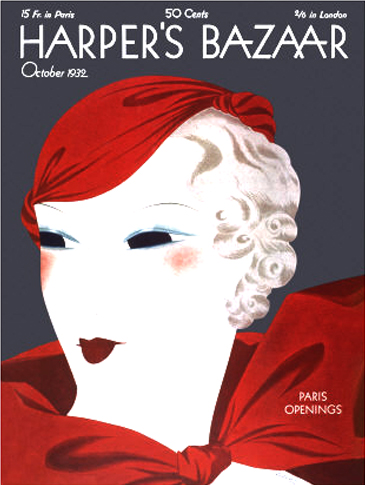

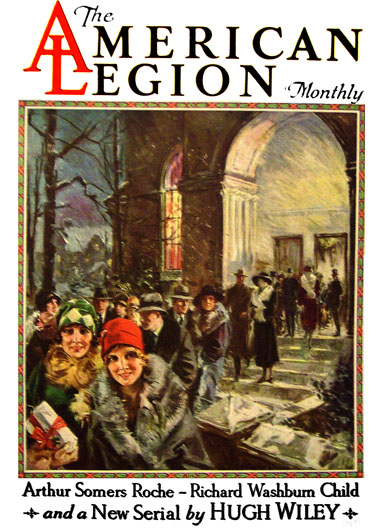

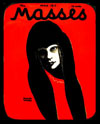

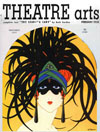

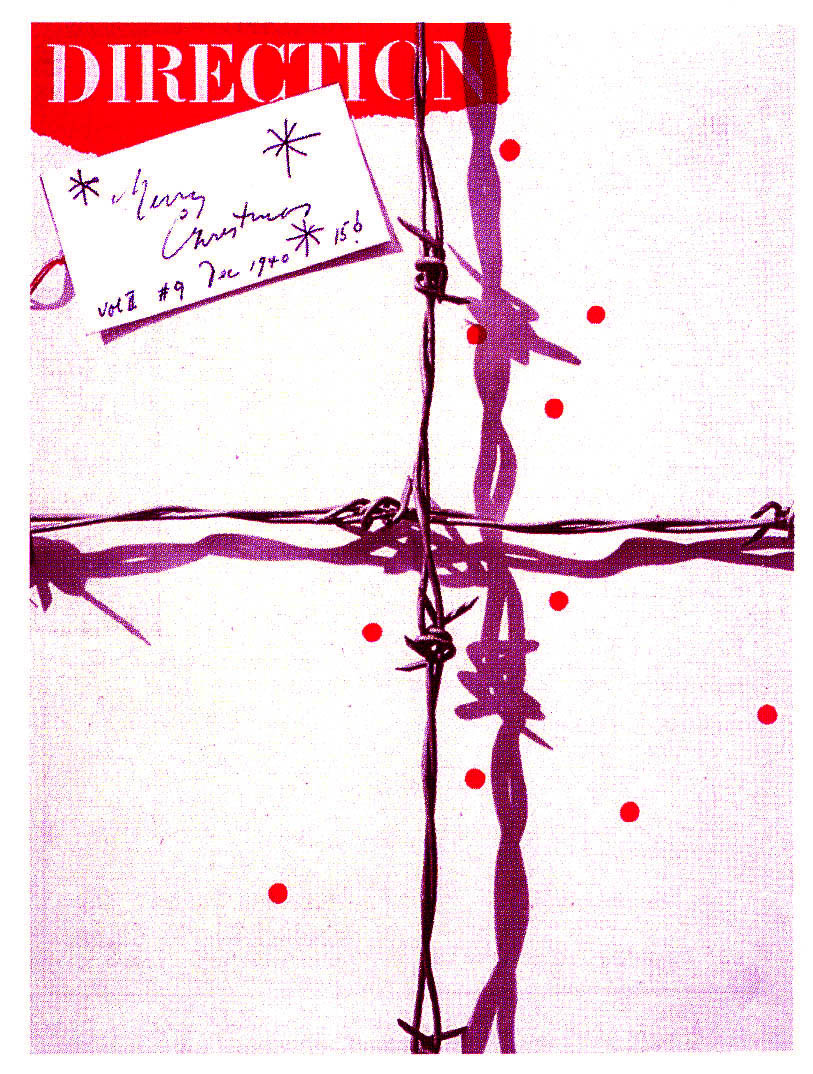

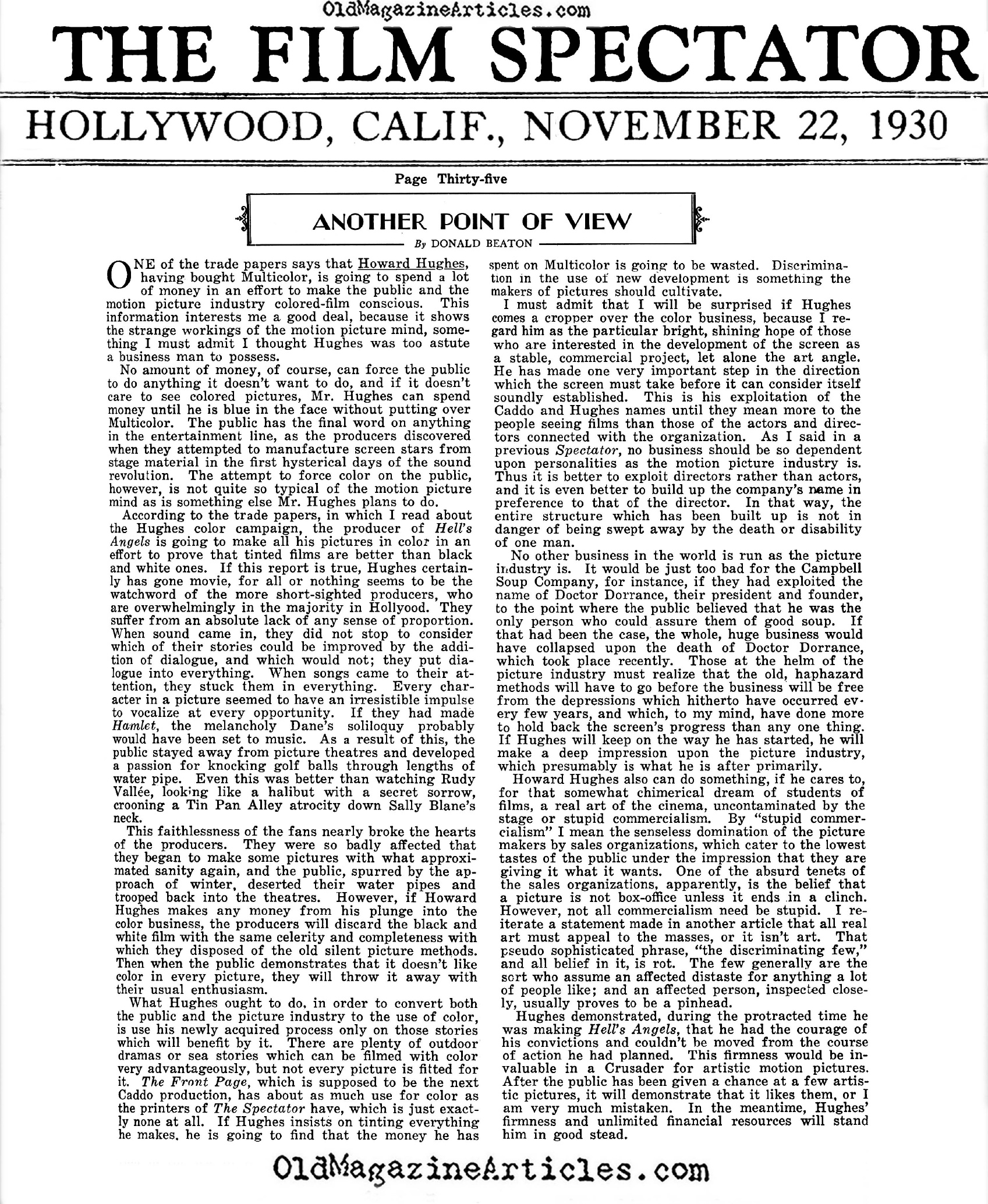

1920s Magazine InformationHaving pored over literally thousands of 1920s magazines in search of historic articles, the crew at OldMagazineArticles.com stands prepared to let you in on what we have learned about these magazines and what they say about the society that spawned them. One of the most startling omissions we never expected was the lack of articles referring to the influenza pandemic of 1918, which caused the deaths of some 675,000 Americans and 50,000,000 people worldwide. It filled the hospitals, challenged the medical and funerary communities, forced face masks onto hundreds of thousands of people and changed the manner of living for millions as they attempted to avoid the disease; did the magazines make mention of this catastrophe? you bet they didn't. Do we know why? We sure don't. 1920s Magazines Catered to a Different Culture The respect that once existed for poetry is illustrated in the fact that within the first three years of the World War I (1914 - 1918), the combined literary efforts of all the soldiers from all the assorted combatant nations produced over 500 volumes of poetry - so strong was their collective urge to versify. In our era, the digital age, soldiers are far more likely to blog in prose or post a video. In the Twenties magazines were widely seen as a prestigious venue in which to be published and thousands of word smiths would submit their efforts. As time went on and affordable phonographs and radios began to serve as popular evening distractions, less and less poetry seemed to be written and the need for poetry editors seemed to slide; by the 1950s, magazines no longer saw the need to employ them at all. The fall from grace that magazine religion editors suffered

seemed to have happened at an even quicker pace. It was in

the 1920s that the roll religion played in the daily life

of Americans began to wain. The roll of religion was not only changing in the world, but in the newsrooms as well; by the late Forties, religion editors would join poetry editors on the unemployment line. The Wall Street Journal is one of the few existing publications to still print the musings of a religion editor; to their credit he recently opined that the only religious voice Americans hear on a regular basis is that of the animated cartoon character "Flanders", from "The Simpsons". On a far more trivial note: having read as many 1920s magazines as we have and judging by the plentiful number of advertisements promoting bunion and blister cures, we have shrewdly surmised that all those reporters, editors and publishers must have worn very, very uncomfortable shoes. |

|

Magazine

Articles Online | Old

Vanity Fair Magazines | Articles

About 1920s | Articles

About The Roaring 1920s | Articles

On Abraham Lincoln | Articles

On Silent Movies | Charlie

Chaplin Articles | Civil

War Articles | First

World War Uniforms | Gettysburg

Address Articles | History

Of the Biplane | Historical

Articles | History

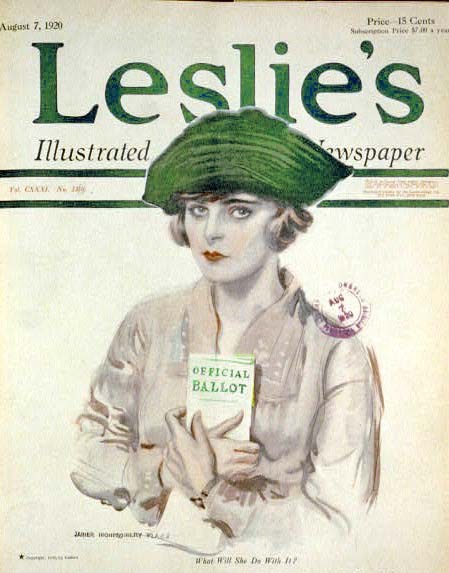

Of Womens Suffrage Movement | Information

On The Battle On The Battle Of Gettysburg | 1920s

Magazine Information | Magazine

Articles About Women | Women's

Fashion 1920 | Charlie

Chaplin Biography | Old

Titanic Magazine Articles | Women's

Suffrage Articles | Early

Aviation History | Old

Vogue Magazines | About

Us Primary Source Website | Old

WW II Magazine Articles | 1920s

Vogue Magazine Articles | Magazine

Articles About the Great War of 1914-1918 | The

Doughboys of World War One | WW

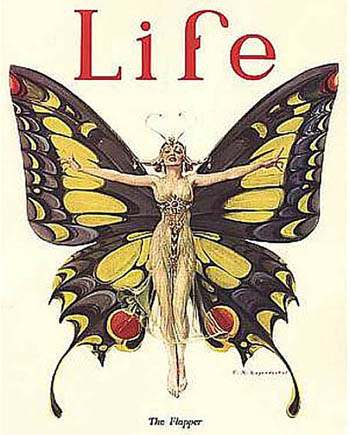

2 Articles From the Homefront | Flapper

Style | Menswear

Fashion Articles

|

|

| © Copyright 2005 Old Magazine Articles | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|